Early Life and Education

Sigmund Freud was born on May 6, 1856, in the town of Freiberg in Moravia, which is now part of the Czech Republic. He was the first of eight children in a middle-class Jewish family, and his father, Jacob Freud, was a wool merchant. The family relocated to Vienna when Freud was four years old, where he spent most of his life. The cultural context of 19th-century Vienna, with its rich intellectual culture and burgeoning interest in the sciences, significantly influenced Freud’s formative years. Vienna was a hub for diverse ideas in philosophy, arts, and psychology, fostering an environment ripe for exploration and innovation.

Freud’s academic journey began at the University of Vienna, where he initially enrolled to study law. However, he quickly changed his focus to medicine, driven by an interest in neurology and the workings of the human mind. His medical studies provided him with a robust foundation in the biological sciences, which he later combined with insights from psychology. Freud earned his medical degree in 1881, after which he pursued research in neurology under prominent figures such as Ernst Brücke.

During his studies, Freud was deeply influenced by a range of thinkers, including philosophers and psychologists like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Nietzsche. Moreover, the burgeoning field of psychology captured his attention, leading him to explore pioneering ideas that would eventually coalesce into his own theories. Freud’s early exposure to various intellectual currents not only shaped his understanding of the human psyche but also laid the groundwork for his later development of psychoanalytic theory. His education, combined with personal experiences and societal influences, would ultimately produce a revolutionary thinker whose concepts have endured over decades, making him a pivotal figure in psychology.

The Foundation of Psychoanalysis

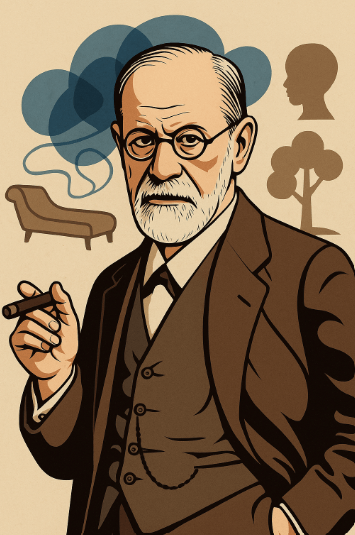

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, laid the groundwork for understanding human behavior through his revolutionary theories that emphasized the significance of the unconscious mind. Freud posited that a substantial portion of human thoughts and actions is driven by subconscious motives, desires, and unresolved conflicts. This notion challenged the traditional approaches of psychology, which predominantly focused on observable behavior and conscious thought processes. By shifting the focus to the unseen workings of the human psyche, Freud opened new avenues for understanding mental health and illness.

Central to Freud’s theory is the idea of defense mechanisms—unconscious strategies that individuals employ to cope with anxiety, emotional conflict, and the implications of repressed memories. These mechanisms, such as repression, denial, and projection, serve to protect the ego from distress and preserve psychological equilibrium. Freud’s systematic exploration of these processes marked a significant departure from existing psychological paradigms, suggesting that the mind is not always a reliable narrator of one’s experiences and feelings.

Another cornerstone of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory is the interpretation of dreams. According to Freud, dreams are the “royal road to the unconscious,” revealing repressed thoughts, unresolved issues, and latent desires. By analyzing dreams, Freud believed individuals could access deeper layers of their psyche, gaining insights into their emotional states and behavioral patterns. This focus on dream analysis not only revolutionized the therapeutic practice but also contributed to a richer understanding of human motivation.

Freud’s innovative concepts laid the foundation for modern psychology and therapeutic techniques, encouraging subsequent generations of psychologists to explore beyond the conscious mind. His legacy continues to shape contemporary discussions around mental health and the complexities of human behavior, securing his position as a pivotal figure in the field of psychology.

Structure of Personality: Id, Ego, and Superego

Sigmund Freud, a seminal figure in psychology, proposed a structural model of personality that deconstructs the human psyche into three interrelated components: the id, ego, and superego. This model is foundational in understanding human behavior and has profoundly influenced both psychological theory and therapeutic practices.

The id is the most primitive part of the personality, representing the instinctual drives and desires present from birth. It operates on the pleasure principle, seeking immediate gratification and functioning without consideration for reality or social norms. The id is responsible for our basic urges regarding hunger, sex, and aggression. It is challengeable in adult life, as the stark desires within the id can often lead to conflicts with societal expectations.

In sharp contrast, the ego develops to mediate between the irrational demands of the id and the rules of the external world. The ego operates on the reality principle, working to satisfy the id’s desires in realistic and socially appropriate ways. This involves delaying gratification and navigating various situational demands. The ego is thus critical in decision-making processes and helps maintain a balance in the personality.

The superego emerges later in development, serving as the moral compass of the individual. This structure internalizes societal rules, values, and norms, guiding the individual toward morally acceptable behaviors. The superego evokes feelings of pride when one behaves well and guilt when one deviates from established standards. This dynamic between the id, ego, and superego can lead to mental conflict and anxiety, as the individual grapples with their basic urges versus moral imperatives.

Understanding the interplay of these three components elucidates the complexities of human behavior. Freud’s model highlights the constant struggle between instinctual desires, realistic thinking, and moral judgments, offering valuable insights into psychological development and therapeutic practices.

Impact and Criticism of Freud’s Work

The theories put forth by Sigmund Freud have left an indelible mark on the field of psychology and psychotherapy. Freud’s pioneering approach to the unconscious mind, dream analysis, and the mechanisms of defense have not only contributed to the foundation of psychoanalysis but have also influenced various domains such as literature, art, and popular culture. His emphasis on the role of early childhood experiences in shaping personality remains relevant, as contemporary therapeutic practices often acknowledge the importance of addressing past traumas. Furthermore, Freud’s exploration of neuroses paved the way for subsequent models of mental health treatment, emphasizing that understanding the root of psychological distress requires a nuanced and introspective approach.

However, Freud’s work has not been without controversy. Throughout the years, various critiques have emerged, both from psychological peers and feminist scholars. Critics argue that Freud’s theories often lack empirical support and are excessively focused on the sexual motivations of human behavior. Many have pointed out that his conclusions are largely based on a limited sample of patients, primarily women from aristocratic backgrounds, and thus may not generalize across diverse populations. Furthermore, contemporary psychology has increasingly deemed certain aspects of Freud’s theories, such as his views on female sexuality, as problematic and reflective of patriarchal norms.

Feminist critiques particularly highlight how Freud’s concepts of penis envy and the Oedipus complex perpetuate gender stereotypes, framing women’s development in relation to men. While acknowledging this criticism, it is also essential to recognize the evolution of psychoanalysis. Modern adaptations have sought to address these biases, incorporating more inclusive and varied perspectives. In contemporary therapy, various approaches are now available, transcending Freud’s original framework while still acknowledging his contributions to our understanding of the human psyche. The lasting impact of Freud’s work, therefore, invites ongoing dialogue, fostering both appreciation and critical evaluation of his complex legacy.