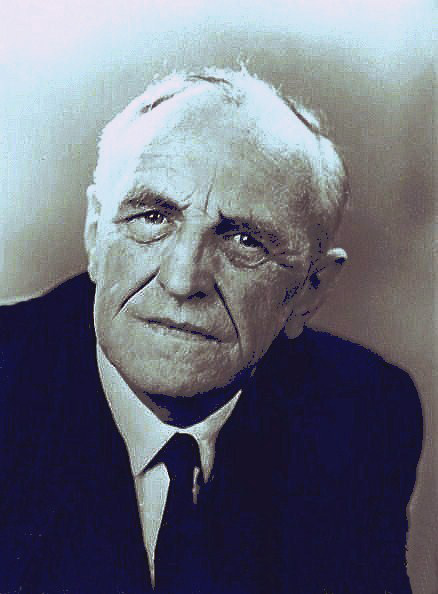

Who was D.W. Winnicott?

Donald Woods Winnicott was a prominent British pediatrician and psychoanalyst whose extensive work in child development has had a lasting impact on psychological theory and practice. Born on April 7, 1896, in Plymouth, England, Winnicott pursued a degree in medicine at the University of Cambridge. His education began at the prestigious Trinity College, where he was deeply influenced by his experiences and observations of children.

Winnicott’s career as a pediatrician provided him with valuable insights into the early stages of emotional development. His early work primarily focused on the physical health of children, but as he delved deeper into the psychoanalytical aspects of child development, he began to understand the significance of emotional care in the shaping of a child’s psyche. This realization led to his commitment to integrating psychoanalysis with the practices of pediatric care.

Throughout his professional life, Winnicott held various influential positions, including his role as a consultant pediatrician at the Paddington Green Health Centre in London. It was during this time that he began to publish his groundbreaking work, exploring key concepts such as the “good enough mother” and the “transitional object.” These ideas underscore the importance of potential caregivers in the emotional and psychological development of children, framing mothering as a dynamic interaction rather than a mere set of tasks.

Moreover, Winnicott was a member of the British Psychoanalytical Society, where he engaged with other significant figures such as Melanie Klein and Anna Freud. His contributions to the field of psychology during the 20th century were not only pivotal in pediatric psychoanalysis but also fostered a deeper understanding of the intrinsic bond between caregivers and children, highlighting the implications of early emotional experiences on later life development. Winnicott’s legacy continues to resonate in contemporary discussions of psychological well-being and early childhood care.

The Concept of the ‘Good Enough Mother’

In the realm of child development, D.W. Winnicott introduced the pivotal concept of the ‘good enough mother.’ This term encapsulates the idea that a caregiver’s ability to meet a child’s needs does not require perfection but rather a sufficient level of responsiveness and attunement to the child’s emotional states. Winnicott asserted that a mother, or primary caregiver, who can adequately support her child’s developmental needs, while also allowing for moments of failure or imperfection, plays a crucial role in fostering healthy emotional development.

The ‘good enough mother’ operates on the principle that it is not only acceptable but beneficial for caregivers to have flaws. This approach acknowledges that a child’s growth can be positively impacted when caregivers face challenges in their parenting journey. For instance, when a caregiver occasionally misreads a child’s emotional signals, it provides opportunities for the child to learn resilience and adaptability. These experiences teach children to cope with disappointment, develop problem-solving skills, and understand that imperfection is a part of life.

Additionally, the concept emphasizes the importance of the caregiver’s presence and emotional availability rather than achieving unattainable ideals. By demonstrating authentic emotional responses, a ‘good enough mother’ conveys to the child that it is normal to experience a range of feelings. This supportive environment nurtures a child’s capacity for emotional regulation, fostering a secure attachment style that is essential for developing future relationships.

Real-world scenarios illustrate the effectiveness of this approach. For instance, a parent who occasionally loses patience but later acknowledges their mistake and apologizes models accountability. Such interactions reinforce the understanding that emotional experiences are complex and that authentic connection thrives amid imperfections. Adopting this mindset ultimately underscores that the journey of parenting is less about perfection and more about fostering emotional growth through genuine, caring relationships.

Transitional Objects: The Bridge Between Reality and Imagination

Transitional objects, a concept introduced by D.W. Winnicott, play a crucial role in the emotional and psychological development of children. These objects, often familiar items like teddy bears, blankets, or even pacifiers, serve as vital tools that aid children in managing the anxiety of separation from their primary caregivers, usually their mothers. Winnicott proposed that these objects are not merely toys; rather, they are significant emotional anchors that help children bridge the gap between the internal world of their imagination and the external reality they encounter.

In the early stages of development, children experience intense separations from their primary attachment figures, which can induce feelings of fear and uncertainty. Transitional objects provide a sense of comfort and stability during these challenging moments. As toddlers may cling to a favorite blanket or toy when facing separation, these items facilitate coping mechanisms that are essential for emotional regulation. They embody a child’s relationship with their caregivers while introducing a sense of security, acting as a reassuring presence when the parent is absent.

Moreover, transitional objects can vary widely from child to child, reflecting individual preferences and attachment styles. Some children might prefer soft, tactile items like stuffed animals, while others may gravitate toward materials such as a particular piece of clothing or a soothing object. Each serves a common purpose: to assist in the transition from dependence on caregivers to a more independent self-concept. This transition is vital as it fosters resilience and adaptive skills that children carry into later stages of their life.

Ultimately, transitional objects facilitate an emotional developmental process that encourages children to explore their environment while still maintaining a connection to the comforting aspects of their caregiving relationships. This interplay between reliance and autonomy is a fundamental aspect of healthy emotional growth, laying the groundwork for future relationships and coping strategies.

True Self vs. False Self: Understanding Identity Formation

In the realm of emotional development and identity formation, D.W. Winnicott introduced the critical concepts of the true self and false self, offering profound insights into how caregiving practices shape an individual’s sense of self. The true self represents the authentic, spontaneous aspects of a person’s identity — those innate qualities that emerge naturally. In contrast, the false self serves as a protective façade, molded in response to the expectations and demands imposed by caregivers or society. This adaptation often arises from the need for acceptance and support within early relationships, which can influence personal development significantly.

Winnicott emphasized that early caregiving experiences play a pivotal role in this dichotomy. When children receive empathic and attuned care, they are encouraged to express their true selves. Such nurturing environments foster confidence and authenticity, allowing children to develop a robust identity anchored in genuine experience. Conversely, inadequate or emotionally unavailable caregiving can lead to the formation of a false self. In such cases, individuals may create a version of themselves designed to meet external expectations rather than reflecting their true nature. This protective strategy can lead to a disconnect, resulting in feelings of emptiness and inauthenticity in adulthood.

The implications of these concepts extend into adulthood, where the prevalence of a false self may contribute to mental health challenges, including anxiety and depression. Individuals who have primarily relied on their false selves may find it difficult to form authentic relationships or pursue fulfilling careers. Recognizing the importance of fostering environments that prioritize attunement and acceptance in caregiving can pave the way for healthier self-concepts. It is crucial for parents, educators, and caregivers to provide opportunities for children to explore and affirm their true selves, promoting emotional well-being and a stronger sense of identity throughout their lives.